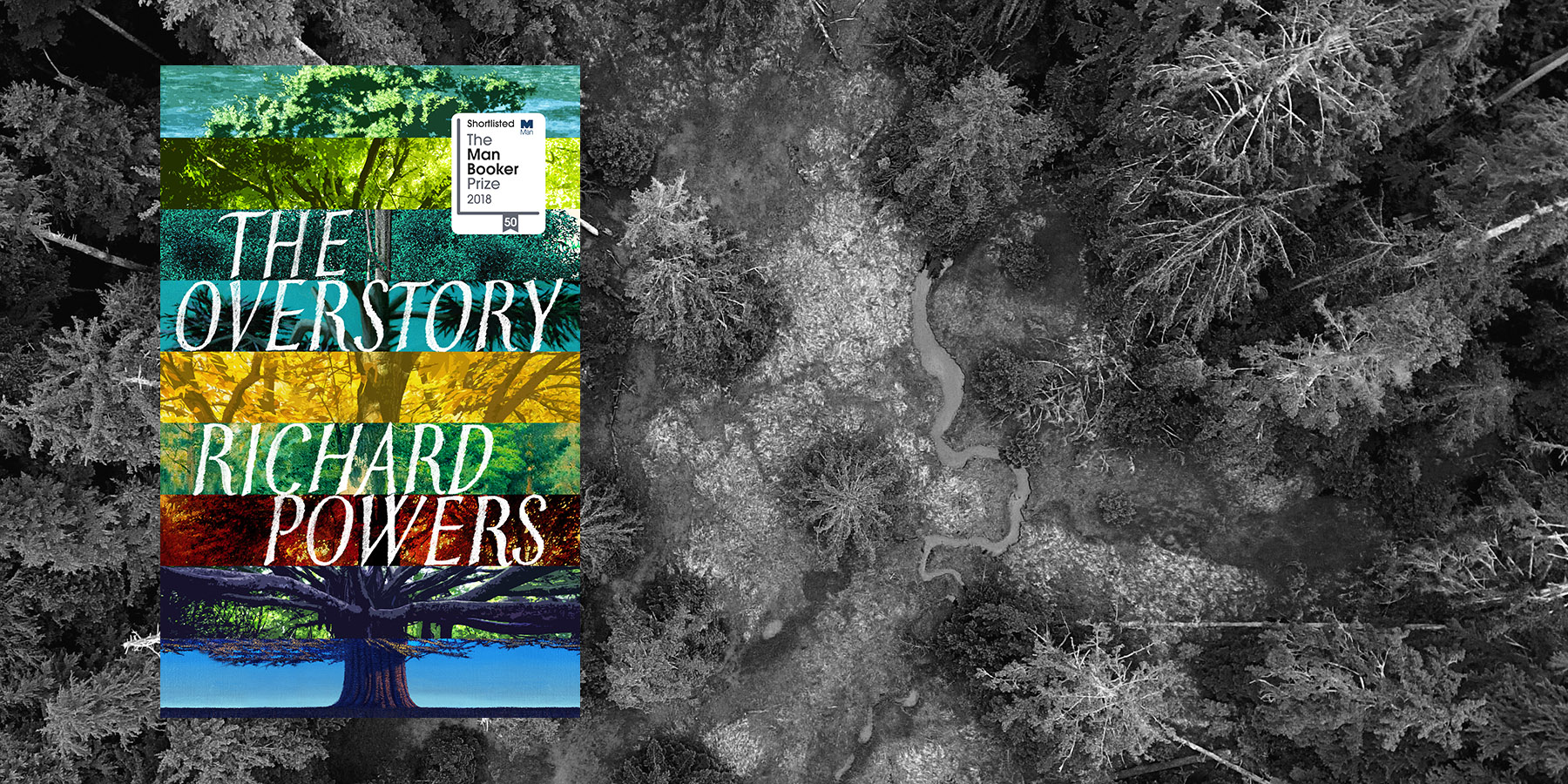

The Overstory

Richard Powers – a review by Annie Worsley

Nine pairings between human characters and trees, The Overstory is a book that offers a new perspective on other-than-human lifeforms. Annie Worsley, Professor of Environmental Change, reviews Richard Powers' latest novel that was shortlisted for The Man Booker Prize 2019.

Some years ago, while preparing lectures and reading material for my students, I came across the work of Canadian Professor Suzanne Simard. Her work on the symbiotic relationships between trees and fungi was exciting and I wanted to include her then novel thinking in my own teaching. Her scientific papers deployed a great deal of data, analysis and experimentation but the core lesson was about the way in which trees communicated with each other across space and time – this was great (bio)geography as well as superb ecology. I was also taken aback by her remarks about the life of a forest because they were a stark reminder of lessons I myself had learned in the mountain forests of New Guinea as a young doctoral researcher. There, indigenous tribal communities who in the 1970s were classed as ‘Stone Age’, had taught me about the interconnectedness of all living things but especially about how the forest trees ‘spoke’ to one another. A Papuan villager called Wai explained how they believed people were part of a living web of life and that the forests in which he lived were not only alive but sentient in a wholly different way to us. Reading Simard’s papers sent me time travelling back to the remoteness of those montane forests and I wanted my own students to engage with her ideas.

Fast forward a number of years and if you have never come across her work, then Simard’s TED talk on how trees communicate is a revelation and if I were still teaching forest biogeography then I would insist on students watching it. Now her ideas have entered the mainstream – scientists have revealed how the exchange of gases, minerals and nutrients from ‘mother trees’ to saplings, and between clusters of trees in diverse woodlands, are effective means of passing on messages and signals between individuals and their ‘families’. Simard herself calls this the ‘wood wide web’. This has transformed our thinking about forest ecology, dynamics and management and has led to a new wave of research and generated new ideas about the relationship we humans have with the living world. Although it is not part of the post-Enlightenment Western culture, in a remoter past ancient British and Celtic peoples too had deeper connections to the natural world and imbued them with spirits and other beings. Somehow, through industrialisation and globalisation the notion that ‘nature’ is sentient and contains organisms that communicate, feel and form communities just as we do, has been swept aside.

But here is a book that turns our anthropocentric way of thinking on its head. The Overstory is a grand book, in every sense of the word. There are nine human characters steering us through Power’s own ecological sensibilities and it is highly likely that he was influenced by forest ecologists like Simard and activists such as Julia Butterfly Hill, who lived for over two years in a redwood tree called Luna. These nine individuals drive the necessary human narrative forward along with hundreds of tree-lives that offer the opportunity to transform our understanding of forests. For most of us, trees are simply part of the gardens and parks or woodlands we visit from time to time. Few of us really see the oak that has stood by the roadside, part of a hedgerow, planted hundreds of years ago other than to recognise its shadow as the seasons pass. Fewer still will wonder at the life it might lead and though all of us, at some point, will run our hands over finely polished wood grain on a sideboard or table top, we almost never think about the cell structures that carried water, sugars, minerals and gases up and down the tree-trunk as it sent messages or warnings to its kin or as it probed the earth below. The Overstory gives us a new perspective on these other life forms. In it we meet beings who are much longer lived than us, who offer alternative perspectives to our human-centric ways. The carefully constructed similarities to contemporary figures open our eyes to their works and efforts and perhaps, bound as they are to specific tree species, conceal truths that may be uncomfortable in the cold, hard glare of academic writing or newsprint.

Of all the nine pairings between human characters and trees, the most poignant for me was the story of the Hoel family whose trans-generational photographs of a very particular chestnut show how it became a living part of their history and sets the scene for the rest of the book by opening our eyes to the longevity of these remarkable organisms. The photographs become like a time-lapse film, capturing the intimacy of that single arboreal life and laying bare our own human short-lived fantasies that ultimately succumb to mother nature and deep time. That the chestnut can speak to us through a story about a series of photographs we cannot see for ourselves is testament to the skill of Power’s writing. It took me back to my own childhood, sketching a great pear tree that stood in our garden, to my young adulthood when an enormous horse chestnut was felled by a hurricane in 1976, to today in the treeless valley where I now live and where I have planted an offspring of that tree, grown from a conker. We will all have stories like that, of interactions with trees, bark rubbing, acorn planting, conker fighting, and yet how many times have we registered the being from which those small tales originate? This book will reanimate your encounters with trees and you will see them with renewed vision.

There is so much learning to be had from this grand book. Even though I taught biogeography to university students my eyes were opened and I felt the familiar thrumming need to find out more. In his sweeping, lyrical way Powers unfolds the particular ecologies of certain tree species but he also opens up the greater histories of forests in the United States. I had forgotten the devastation of vast chestnut forests by blight in the early nineteenth century and the clear-felling by pioneers as they travelled and then staked their claims. Today, much of America is forested by secondary re-growth typically along the freeways and although they are rich in species number they are not ancient. What the original virgin forests must have looked like is perhaps too far from our minds to comprehend. And yet, The Overstory offers the opportunity to slip inside one of Power’s main characters and understand what he is telling us about trees. Even if you cannot fully empathise with the human character the reader ends up knowing more about the partner tree than could be gained by reading any academic tome on forest ecology, rooted to the tales.

There are lessons to be learned too. If economic terms must be employed here then the book shows us how we are ravaging nature’s ‘capital’ and ignoring the costs. If we sidestep pressures to use econometrics when writing and reading about the nature, then this book takes us inside a world that is much longer-lived than our own, one that will outlast us, the over-story that will ultimately overwrite humanity. The book’s true power is that it comes at a time of conflict and great loss, a sixth global extinction, and at a time of considerable climate change and environmental degradation. It tells us that no matter what we do, the living world will carry on with or without us. I would go so far as to say we need more books like this, that are unafraid to harness the power of the literary and the scientific, books that will make our natural world more accessible and enhance our understanding of how our biosphere works, and books that could show us that we do not rule the earth. We are the understory after all.

Header Image: Owen Perry

Additional Images: Jay Armstrong

Richard Powers is the author of twelve novels, including Orfeo (which was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize), The Echo Maker, The Time of Our Singing, Galatea 2.2 and Plowing the Dark.

He is the recipient of a MacArthur grant and the National Book Award, and has been a Pulitzer Prize and four-time NBCC finalist. He lives in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains.

Annie Worsley is a writer, physical geographer, crofter and Professor of Environmental Change. Her academic research focuses on human impacts and the nature and rates of change in UK coastal, peatland and urban environments, and in the mountains of Papua New Guinea. Although living remotely Annie continues to work with her research colleagues in UK universities.

Annie is a keen amateur photographer, a valued contributor to Elementum and regularly blogs and continues to write scientific articles in academic journals. Annie is currently writing a book about the life and wildlife of Red River Croft.

Annie lives in the North West Highlands of Scotland with her husband Rob, dog Dram, Shetland ponies and assorted wildlife. She is a mother of four, and now grandmother of four very small, wonderful humans.

You can follow her @RedRiverCroft on Twitter and @red_river_wild on Instagram