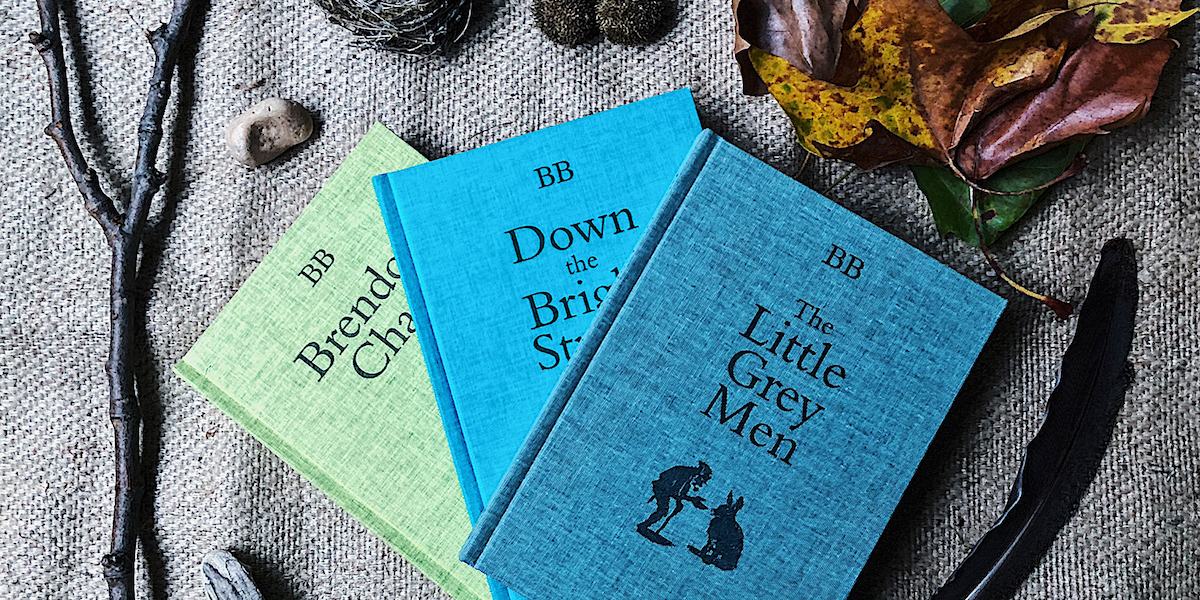

'The Little Grey Men' and 'Down the Bright Stream'

BB – Writer Helena Drysdale reflects on the work of British naturalist, illustrator and children's author.

In 1970 I told BB how much I loved his books. I wrote the letter sitting at the window in a house tucked into a Devon cliff, with pine woods behind and the sea in front. I’m sitting there now. It’s the sort of place BB would have adored, the recesses of undergrowth and exposed headlands teeming with wildlife. This, I imagined, was the setting for The Little Grey Men (1942). Here were all the ingredients, including wood dogs (foxes), fernbears (badgers) and above all a winding stream. In my mind this was the Folly Brook, up which the last gnomes in England travel on their heroic quest to find their missing brother, and down which they flee in their boat, the Jeanie Deans, in the 1948 sequel, Down the Bright Stream.

My mother encouraged me to write to BB because she shared my passion. As a child she had sent BB a map of her imagined Folly Brook, which she made on vellum, like the one Baldmoney – the cleverest of the gnomes – draws with a piece of heated wire on the inside of his mouse-skin waistcoat.

BB thanked me for my letter. He told me he lived in a round house (and drew a picture of it), which was built in the year that Samuel Pepys began his diary. It had a weather-vane in the form of a wild goose which he himself had designed so that its beak always faced into the wind. ‘Yes, I am married,’ he wrote, so I must have asked. He had one daughter called Angela, he said, but his son Robin had died when he was 7, two years younger than me. ‘I hope you will read my books to your children,’ he wrote, ‘though by then I shall have flown away like my wild goose.’

BB wrote an astonishing sixty books, both for children and adults, and illustrated them all, but the Carnegie Medal-winning The Little Grey Men remains his most popular. The first edition had exquisite black-and-white scraperboard illustrations, like woodcuts, by Denys Watkins-Pitchford. In later editions published more lavishly after the war, most of them were replaced by watercolours, also by Denys Watkins-Pitchford, but it is the monochrome scraperboards that best capture the scary vastness of the landscape inhabited by these tiny men. One-legged Dodder kippers minnows for supper, a few deft lines evoking the circle of firelight that illuminates his bulbous nose and shaggy beard, and exaggerating the blackness of the surrounding forest. Baldmoney and Sneezewort disappear furtively behind gigantic grass stems. Dodder cadges a ride from the aristocratic Sir Herne the heron, his head reaching as high as the heron’s knees.

There can be few other combinations of text and illustration that work so harmoniously, revealing such a powerful imagination and such an intimate relationship with the minutiae of the natural world that you don’t question the existence of the Little People. This is because BB and Denys Watkins-Pitchford were one and the same; he adopted the pseudonym because it was less of a mouthful. For me, the mystery of his dual identity only added to his fascination.

As BB says in his introduction to The Little Grey Men, most fairy books portray miniature men and women with ridiculous tinsel wings, doing impossible things with flowers and cobwebs. He may have been referring to Cecily Mary Barker’s Flower Fairies, first published in 1927. As he rightly adds, ‘That sort of make-believe is all right for some people, but it won’t do for you and me.’ His gnomes are never sentimental or twee. They are just a short imaginative step from the woodland creatures that are their friends. In his memoir The Idle Countryman, published in 1943, a year after The Little Grey Men, BB stresses his love of wandering alone in the wild, especially at dusk, and the mix of enchantment and fear it can generate.

Yet his gnomes also lead a cosy domestic life. As a child I yearned to live as they did in a hollow oak, swigging elderberry wine from snail shells. I longed to sup on mushrooms in the cabin of the Jeanie Deans. That combination of wild and domestic is like Kenneth Grahame’s 1908 The Wind in the Willows, which BB would have grown up reading. The little grey men mess about in boats, have adventures, enjoy companionship, and have nothing whatever to do with women. Dodder shares Ratty’s gruff self-reliance and decency, while restless Cloudberry has a touch of Mr Toad. It is Cloudberry’s adventurous spirit that inspires the journey in the first book, and his Toadish rashness that triggers all sorts of dramas in the second.

As writers, BB and Kenneth Grahame were divided by the world wars, and the gnomes’ lives reflect that in being more perilous than those of the Edwardian Ratty et al. The gnomes confront shipwreck, starvation and murderous pikes, stoats and foxes. Their greatest enemy, however, is Man. The worst is Giant Grum, the gamekeeper with his ‘stick that roars’ and his horrifying gibbet where some of their friends are strung up. But it is mankind that threatens their existence. This is the 1940s, and bombers loom in the background of Down the Bright Stream, but more devastating for the gnomes is environmental destruction. They live not in Devon as I imagined, but in Warwickshire, in the heart of the country and not on its edge, and England – its natural beauty and its destruction – lies at the heart of these books.

BB’s nostalgia for an unwrecked England carries a double blow today: we share his sense of doom as the Folly Brook is diverted into a pipe and the gnomes’ hollow oak is felled, and we add our own awareness of how much things have since deteriorated. BB describes elm trees, unaware that thirty years later they would be wiped out by Dutch Elm disease. My daughters have never seen an elm. He describes flower-filled water-meadows, unaware that most would be drained or covered in housing. Major characters in the books are water-voles but, according to recent RSPB research, 98 per cent of England’s water-voles have vanished. So progress marches on.

The books also generate nostalgia for our own childhoods, when our senses were more alert to the natural world, largely (BB believed) because we were closer to the ground. A sickly child, he was kept at home in his Northamptonshire rectory and given no formal education, and he felt the better for it. In a Times interview accompanying publication of his autobiography A Child Alone (1978), BB says that had he been well and sent to school, he would probably never have written a word. Instead he explored his surroundings and lost himself in fishing, collecting eggs and caterpillars, and learning the calls and habits of birds. Art at the Royal College was his only real education, and his seventeen years teaching art at Rugby (1928‒45) his only real job.

That absorption in the countryside is what makes these books so captivating. BB’s attention to detail – to subtle changes in weather, the migration of swifts or the scent of willow buds – reminds us to notice such things again; things which once seemed magical but which in adulthood have become humdrum or ignored. He prefaced Down the Bright Stream with a text copied by his clergyman father from a Cumbrian gravestone, which sums up his wide-awakeness:

The wonder of the world

The beauty and the power

The shapes of things,

Their colours, light and shades

These I saw,

Look ye also while life lasts.

Look ye also while life lasts: it’s what I tell my creative writing students. Wake up! Turn off your phones! Take time to stand and stare. But often I too go around in a dream, rehashing old conversations and forgetting to notice what’s going on under my nose. Most of us do.

For all his wonder and for all his urge towards conservation, BB was happy to kill. He was a passionate fisherman and shot. Likewise, his gnomes live contentedly with their friends Otter, Squirrel and Mr and Mrs Ben the owls, but they also wear mouse-skins and dine on fish. Shooting gave BB a link with his boyhood and with a countryside then so rich in wildlife that it could accommodate a hunting man. Even his pseudonym came from shooting: BB is the size of the lead shot used for geese. As he described in The Shooting Man’s Bedside Book (1946), for him shooting was a way of steeping himself in nature as well as filling the pot. He enjoyed the tension, the patience, the solitude, and the beauty and wildness of places haunted by wildfowl. He also enjoyed the idea of using his physical strength, his keen eye and sense of ‘marsh craft’ to outwit a wild creature in that creature’s own environment.

This informed the lives of the little grey men, who hunt to survive. You get the feeling that BB would have enjoyed being a little grey man himself, a hunter-gatherer living in a hollow oak. Yet he was also a sociable man with a happy family life. He was not one of those naturalists who feel uncomfortable in company; nor was he a fascist like T. H. White or Henry Williamson.

I never met BB. Following our correspondence, my mother and I made a pilgrimage to see him at the Round House, his former toll house in Sudborough, Northamptonshire, which was not far from the rectory where he grew up. But sadly BB was away, barging in Wales, for which he was deeply apologetic. ‘Dates change continuously with the wayward way of a weathercock,’ he wrote. His caretaker showed us round. The garden was disappointingly artificial, including a gnome-sized waterwheel made for his father sixty years earlier, and which inspired a dramatic scene in The Little Grey Men.

Although BB was 65 when he wrote to me, The Little Grey Men is subtitled ‘A Story for the Young at Heart’, and this is what he was.

The housekeeper told us that the previous summer BB’s wife Cecily, his emotional mainstay, had died prematurely after being enveloped in pesticides sprayed by the neighbouring farmer. He himself died sixteen years later, in 1990, flying away like his wild goose weather-vane just before my first child was born.

Helena Drysdale is the author of several highly acclaimed travel books including Mother Tongues, Dancing with the Dead and Looking for George, which was shortlisted for the J. R. Ackerley Award for Autobiography. She currently lives in Somerset.

Denys Watkins-Pitchford (1905–90), who wrote under the pseudonym ‘BB’, was the author of more than sixty books for adults and children. BB was both a writer and illustrator, and his charming original illustrations decorate these books. But above all he was a countryman, whose intimate and unsentimental knowledge of animals, birds and plants, as well as his gifts as a storyteller, make these books unique.

Growing up in a rural Northamptonshire rectory and thought too delicate to go to school, BB roamed the countryside alone. His nostalgic evocation of the unwrecked England of his childhood, inhabited by the last survivors of an ancient and characterful tribe of small people who live in total harmony with their surroundings, is magical.

This article first appeared in Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly, Issue 55, Autumn 2017.